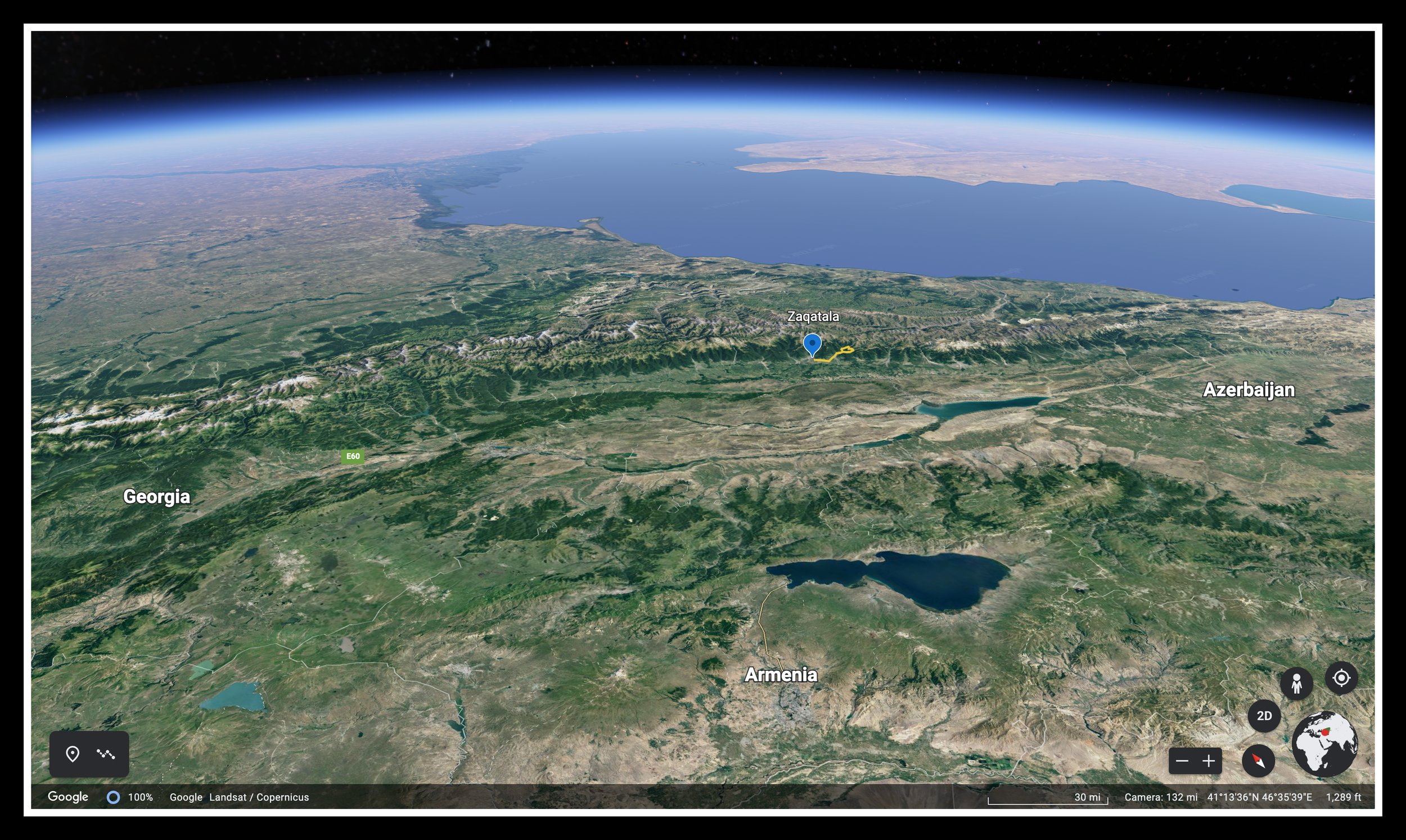

139 - Foothills of the Caucasus - Part I (Near Zaqatala, Azerbaijan)

AMY, ANOTHER OF MY PEACE CORPS MUSKETEER PALS, had an idea—head to a mountain village above Zaqatala and do a little campy camperson. The only public transport was an amphibious assault vehicle (AAV minus the assault cause I like the way it sounds) over a riverbed, departing every other day… or not. Her plan was short on specifics. Where would we camp? What route would we take? How would we get back? No idea.

My kind of plan.

An AAV (minus the assault) left the local bazaar at 3 p.m. on a Sunday. Our “assault” was a bone-jostling ride over a rocky riverbed with a river crossing or two for good measure. I held onto the bread for dear life. Bread? The gentleman next to me had bags of homemade bread he was transporting to his village. At one point, he switched seats and left me in charge of bread stabilization. It was atop a metal barrel and under constant threat of cascading to the floor. Bread isn’t just a dietary staple in Azerbaijan, it skirts the realm of the sacred. Allowing it to touch the floor was like using it to clean my rim. Exaggeration? Perhaps, but only a slight one.

This trip was a refreshing change from the usual “what-the-hell-is-happening-where-am-I-going-what-am-I doing-why-is-everyone-staring-like-I’m-a-two-headed-centaur” semi-euphoric state I found myself in where nary a word of English is spoken. Amy spoke Azeri, providing a rural Azerbaijani vignette I couldn’t appreciate traveling solo. One colorful character was a WWII veteran who’d come into Zaqatala to celebrate Azerbaijan's Victory Over Fascist Assholes Day. (I might’ve taken liberties with the translation.) He’d fought with the Soviets against Hitler's invading army. Imagine the stories locked within his vault.

Amy submitted our “plan” to committee to see what advice we could garner from the denizens. Camping outside the context of some necessary task (animal herding, overland travel, refugee migration, etc.) for shits and giggles is unheard of. I could tell by the exchange a thoughtful debate was unfolding. The initial “advice” we received was as follows: You'll die. You're crazy. Stay at my house. You cannot do it. You can do it. There isn’t a trail. There is a trail. There’s too much snow. You'll die. There are wolves. You'll die. Stay at his house. No, stay at my house. You can do it, but you should stay at my house. You'll die. Stay at her house. You need a horse. You can do it, but why would you want to? You'll die. Stay at my house. Get a horse.

And then came our run-in with the authorities. At a village stop, Colonel Azerbaijan entered the AAV and interviewed us. El Jefe started with me but veered towards Amy when presented with my vapid “I’m-with-her” smile. He examined our passports, then informed her we needed permission to be in the area a la some registration form. She, politely and with diplomatic deftness, gave him the “What-the-fuck-are-you-talking-about” routine. Registration? For what? The lottery? It had the smell of a fictitious regulation soon to be followed with a request for a “fee.” She scored points after identifying the recent celebration as being held in honor of Heydar Aliyev, the deceased former president. Even without the translation, I picked up the sentiment and could see the “Well played, my dear lass” facial expression our interrogator bore.

In an apparent display of self-importance, he exited with our passports and began making calls. In his absence, Amy informed me we were married and shared relevant personal information couples might have if our union was put to the test. (She mentioned the possibility of our nuptials earlier as a way of avoiding questions about our culturally perplexing status.) A half-hour later, Army Man returned, handed back our passports, and ordered us to leave immediately following our two-day camping extravaganza. He further instructed us to inform them of our departure, then looked at me and exclaimed, “Welcome to Azerbaijan” in Azeri. If what a sheep herder later told us is accurate, that was the last military checkpoint before reaching the Russian border. The Azeris are too “lazy” (his words, not mine) to man an outpost on the border with their Russian counterparts.

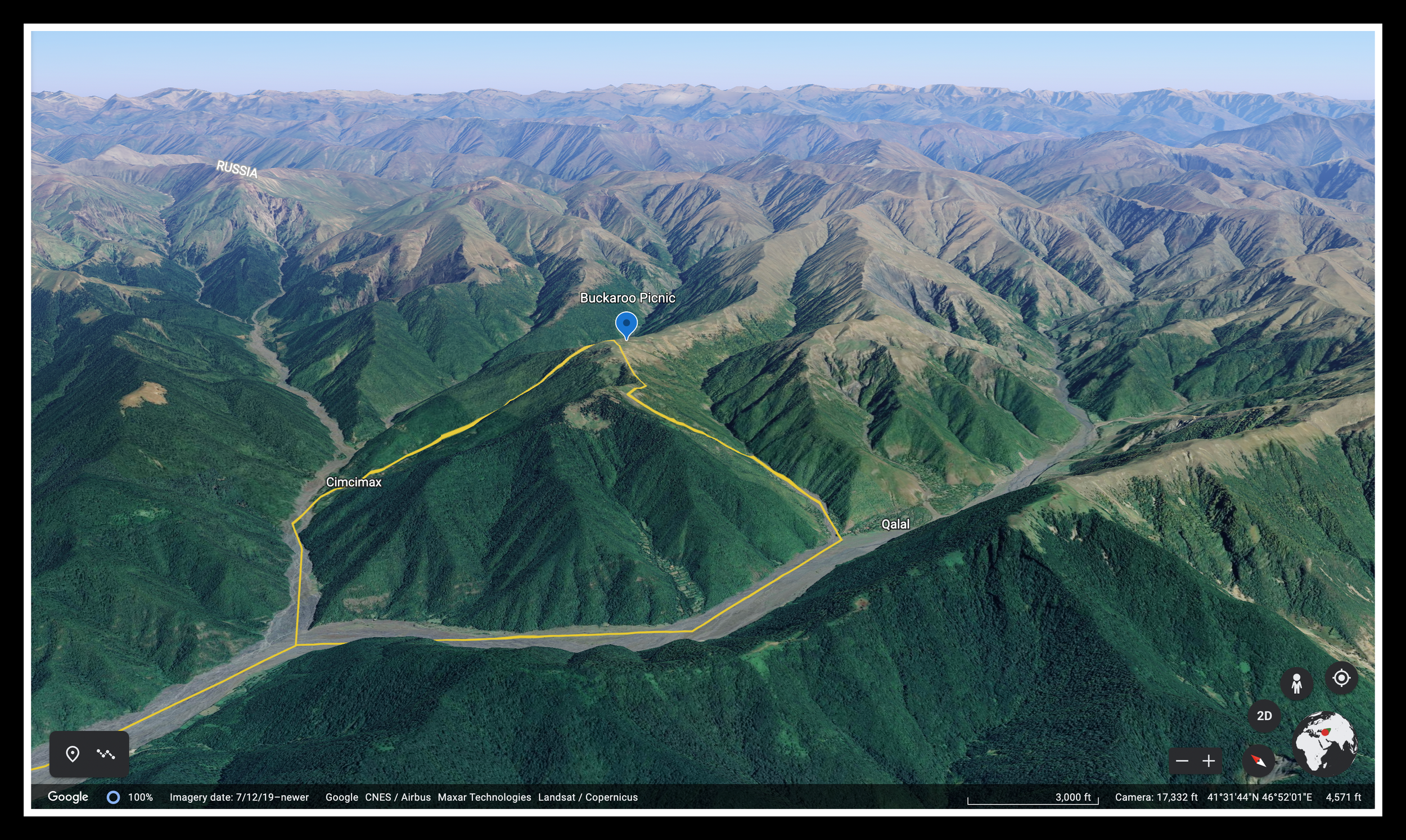

When we arrived at the last village (Cimcimax), more high-level talks ensued. Everyone continued to insist we stay with them, but Amy held fast, explaining she wanted to sleep in the forest, something she enjoyed doing back home. We weren’t against a homestay, it's just we had our hearts set on camping. If she had more free time, I would’ve insisted we play house guests. We were led to a trail leading to the hills, but not before stopping for tea and homemade jam at a local home. The WWII vet joined us. The family provided us with yogurt and cheese for our trip. My heart swelled with gratitude. We set up camp in the forest. Our goal was to reach the top, but the dying light stopped us short. It was just as well as the tree cover protected us from the nighttime rains that befell the region.

The next morning, we joined two buckaroos (as in cow herders) who’d passed us on horseback while we were packing. In the tradition of Azeri hospitality, we were invited for a morning picnic and spent a good hour soaking up the scenery from the treeless pasture atop the hill. I was again thankful for Amy's language skills. Communication with our new friends enhanced the interaction exponentially. They, like everyone, were curious to know what the hell we were doing and why. Amy tried to explain, but camping for the sake of camping was beyond their ability to comprehend. “Married” couples tramping through the Caucasus lowlands is on par with roving herds of unicorns.