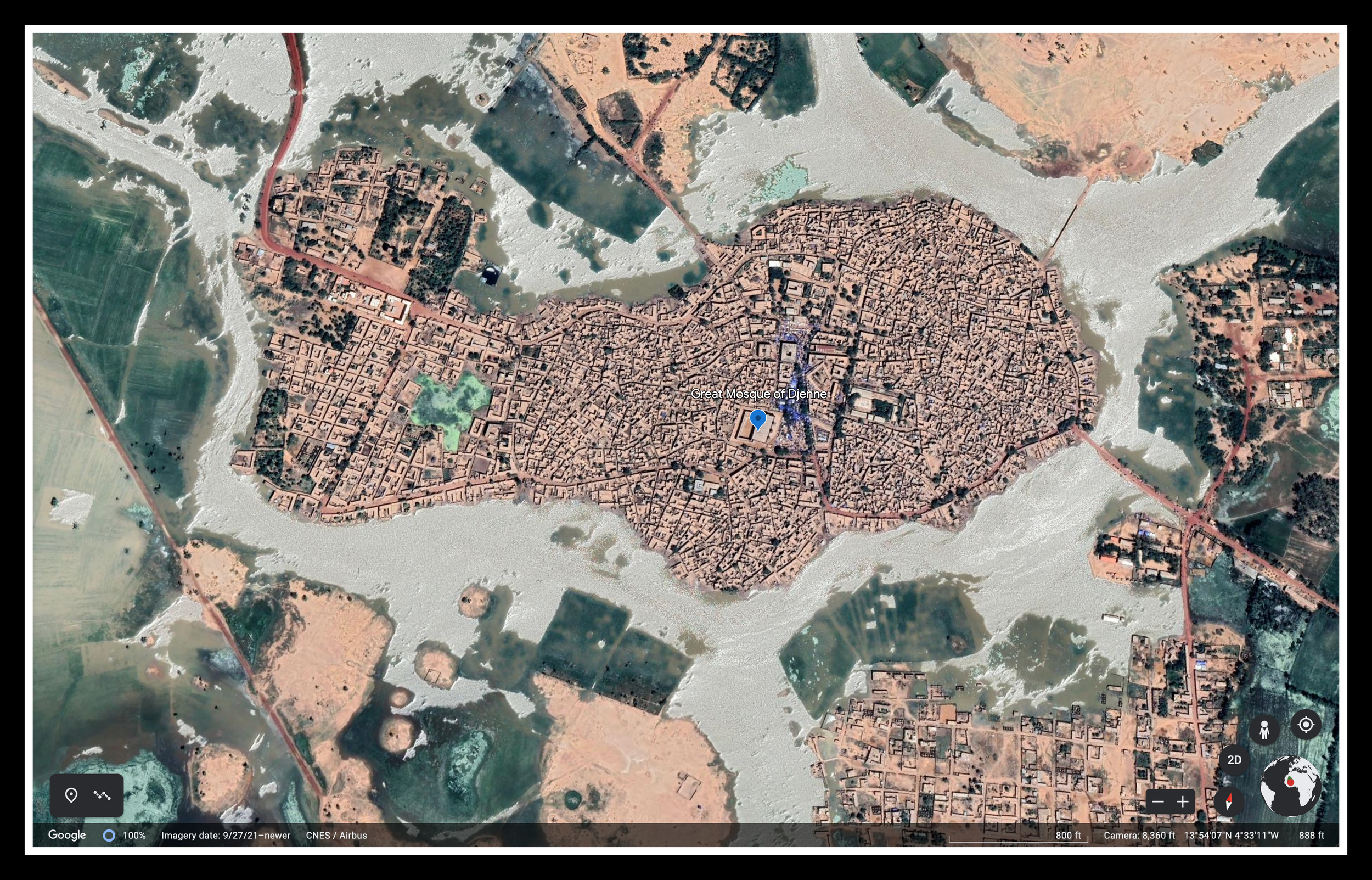

194 - Juju Man (Djenne, Mali)

WE MET SORI IN THE MORNING NEAR THE GREAT MOSQUE and hopped on motorbikes for a guided tour of Djenne’s surrounding area. The region is an archeological and anthropological wet dream—one of the oldest urbanized centers in sub-Saharan Africa. Gaby, the archeology student from Rice University we'd met the previous day, was there excavating Djenne-Jeno, the original site of Djenne to the south.

Outside town lie ancient burial pots protruding from the ground mere meters from the road. Gaby said many likely contain skeletal remains. Preservation efforts lag requirements, so much of the area's historical wealth is waiting to be studied. You'd think someone would take minimal steps for preservation before creating a road right through a burial site. Then again, if my primary struggle was simply living life, I wouldn’t give two shits about dead pottery people either.

Sori took us to a nearby Fulani village, where we were exposed again to the machinations of everyday Malian village life. Mundane. Pedestrian. Fascinating. Another planet, a million miles from the world in which I grew up. After dropping by the homes of Sori's friends, we visited a local craftsman to stock up on juju. Can you ever have too much? I don't think so. Juju refers to the supernatural power ascribed or infused within a chosen object or talisman.

“Juju is a folk magic in West Africa; within juju, a variety of concepts exist. Juju charms and spells can be used to inflict either bad or good juju. According to some authors, ‘It is neither good nor bad, but it may be used for constructive purposes as well as for nefarious deeds.’ Juju charms can at times employ Arabic texts written by Islamic religious leaders. A ‘juju man’ is any man vetted by local traditions and well versed in traditional spiritual medicines.

Juju is sometimes used to enforce a contract or ensure compliance. In a typical scenario, the witch doctor casting the spell requires payment for this service.” (Wikipedia)

Folks ain’t fucking around. Sori spent 50,000 CFA ($100) for his own, an astronomical sum in those parts. Our juju would only set us back about $6 US each. Hopefully, we didn’t get what we paid for…

“We were lucky enough to spend a few days roaming the town and nearby Bozo and Fulani villages. With the help of our guide and two motorbikes, we had a fantastic time. We learned a lot about the history, people, and customs. While visiting one of the villages, we both received custom ‘juju’ from a maker. If you’re not familiar with the African term, it refers to supernatural powers ascribed to an object, and the practices associated with it. I prefer to call it a good luck charm, but that’s just me. Supposedly inside of our tiny leather charms, there is a verse from the Quran, and that the maker selected each verse by what he saw when looking into our eyes. Now, I don’t recall any magical moment where the depths of my soul were exposed, but then again, who am I?

When I wasn’t strapped to the back of a bike getting burnt to a crisp, I spent my time playing soccer with little boys and teaching clapping games to little girls. I can assure you there are worse ways to spend your days.”

Leslie Peralta, “We Made It (Villages, Juju & Sunburns)” — Soledad: Notes From My Travels

Leslie and I sat back, drank tea, and watched two men craft ours. All you need is goat leather and a verse from the Koran, at least in that village. Sori told me much care goes into choosing the verse… unless you’re a tourist. Then, I guess, any old verse will do… or a blank piece of paper, a hex, a knock-knock joke, a recipe for dolma, or a naughty poem for that matter. What was in ours? Who the hells knows? One mustn't forget the Juju Golden Rule: Juju onto others as wish them to juju onto you.

The paper is folded and encased in leather (rectangular), covered with a curing concoction, and fastened to the end of a strap, then tied to a belt or the like and worn underneath the clothes near the waist. We “consecrated” our juju by joining hands while the craftsman uttered phrases in Fulani.

I’m not a superstitious person, and my experience with the supernatural is confined to Hollywood. Still, I have to admit I was a teensy-weensy uneasy about carrying juju, which rhymes with voodoo. (Can you say subtle mindfuck?) When I was in Nepal, I was given two Tibetan prayer scarves before setting out on a trek for good luck. I still have them. I can use all the luck I can get, but I suppose it can swing both ways.

(Postscript — Years later, we dismantled our juju and burnt the remains. By then, we’d gone our separate ways and continued to drift apart. The vicissitudes of life following our trip loomed large in our respective lives. We’d independently concluded it was better to be safe than sorry (or is it “Sori”?), electing to purge a potential bad luck talisman. I can’t, for the life of me, remember what was written on the folded paper inside my juju. I think it was something in a foreign language, but I don’t recall and may just be assuming.

I’d like to say it all turned around after my juju went up in smoke. I’d like to say that. The truth is, I used the juju as a scapegoat. I’m the master of my fate (more or less) and the blame for any “bad luck” lies with me. I believe Leslie’s life panned out for the better if what little I know is correct. For that, I am truly grateful and hope she has all she wants and needs. She was one of the best things to happen to me, worth a lifetime of bad juju.)

We departed for another village, this one settled by Bozos (ethnic group, not clowns). This required a short ferry across a small river that had yet to dry up. As we entered, we saw women and children smoking fish over a ground fire and watched as airborne thieves (some species of raptor) made repeated attempts to filch the catch. We visited the local blacksmith shop, stopped by another mud-brick mosque, and visited Sori's grandmother so he could deliver medicine. (She was under the weather.)

Upon return to Djenne, Sori gave us a brief tour. We learned some history, witnessed young boys memorizing Koranic verses outside a school, took a peek inside the local witch doctor's office, and appreciated the architecture. Again, the abject poverty was front and center. Although much has been done in the way of development, the city still suffers from a lack of adequate drainage facilities. One must avoid puddles of wastewater constantly. They were still trying to work out the kinks of a soil infiltration system developed and funded by the German government.

And there’s another wrinkle. Because Djenne has been designated a World UNESCO site, the residents are forbidden to renovate their homes. Doing so would jeopardize their special status, which could cut into the tourist trade. I guess you could say they’re caught between an ancient rock and a hard place. I can only imagine the resentment arising from being forced to live in a museum.

That evening, we met Sori at our hotel to discuss a tour of Dogon country. We initially inquired about arranging another taxi from Djenne to Mopti, but this somehow morphed into a Dogon excursion. When Sori arrived with his driver, he behaved as if we’d agreed on a trip. We had not. His discounted price for a ride to Mopti (around $40) was contingent upon booking Sori and his driver for a Dogon extravaganza. We still weren’t sure when we’d visit, so we had to decline and settle for the bus. Frown.

Along came Hamma. Hamma was a tour operator in Mali and, as it turned out, offering a package deal that included a three-day pass for the Festival in the Desert, lodging, and a return three-day pinnace trip from Timbuktu to Mopti on the Niger River. All this for a bargain price of $350 US each. We were skeptical. This price was reasonable, a rare occurrence during our Mali visit. But we warmed up to Hamma after discovering he’d not only spent a fair amount of time in NYC but also loved Saratoga Springs and its horse-racing track. Saratoga Springs is about an hour and a half from my hometown. Small world, indeed. We had a good vibe about him, so we each left a deposit of $50 to secure our tickets and lodging. We would pay the rest when we saw him again in Timbuktu on the 5th of January… or would we?