125 - Everest Base Camp (Three Passes Trek, Nepal )

I POSTED MY TREKKING EXPLOITS a week or so after returning to Kathmandu. Thirteen days of adventure required two weeks of writing and editing. Odd occurrences befell me in the interim. One day, as I strolled Thamel’s streets, a Nepali gentleman approached, eager to engage. This wasn’t out of the ordinary. Trekking guides, travel agency employees, street hawkers, beggars, and students often vied for conversation with foreigners.

This was a little different. He paused as I drew closer, not saying a word for a few awkward moments. He stood. He stared. I presumed he was shy, needing time to overcome his embarrassment. Finally, he spoke:

Strange Man: Namaste!

Me: Namaste.

(awkward pause)

Strange Man: How are you? (At this point, I realize something is off. He struck me as a variation of an adult bookstore peep show degenerate. Harsh? Yes, but this is what came to mind. I’m a terrible person.)

Me: I'm gooood… How are you? (I’m thinking he wants to me go on a trek with his agency or is selling something.)

(awkward pause)

Strange Man: I am fine.

(awkward pause)

Me: What can I do for you?

(awkward pause)

Strange Man: I not work for travel agency. I am student. I like practice my English with you.

Me: Ohhhh-kay. English, huh?

Strange Man: Which country from? Germany?

Me: Nope. USA… America.

Strange Man: Ahh, America? Very nice country.

Me: Yeeeeah, it's not too bad. (We continued to walk. I made a left turn down an alley toward a restaurant.)

(awkward pause)

Strange Man: I like boyfriend. (His persistent gaze was akin to my reaction to a Norwegian supermodel.)

Me: Oh no. No. No. No. No boyfriend. Sorry. Bye, bye. (I walked faster. He stopped in his tracks and continued to stare like a wolf eyeing a baby caribou. Did he think I’d come to my senses and realize what opportunity I might be passing up? No way to know. Why me? Did I have the aura of a gay man cruising Thamel for native shlong? I guess so.)

One evening, I returned to my room to find a thumb-sized cockroach patrolling the carpet. Thus began a test of wills. Grendel, as I affectionately called him, did not go gentle into that good night, requiring ten minutes to wrangle. After capture, I cast him into the porcelain sea and flushed vigorously. He fought the current for an impressive length of time. Did I reward his courage and tenacity by rescuing him from a watery grave? No fucking way. Buddha would disapprove, but how could I rest knowing such a leviathan lurked in the dark?

One fine morning, I descended the staircase in my hotel and saw a man dressed only in pink bikini briefs with black stripes pissing into a potted plant on the landing between steps. I kept walking. My brain failed to synthesize the scene, as if to say, “No, Rich, that man’s not pissing into a plant right in the hallway. That’s ludicrous, ludicrous I say! And he certainly isn't wearing earplugs.”

Earplugs? I suppose that explains why he didn’t hear me coming. A swift kick in the jewels wouldn’t have been a disproportionate response. At the very least, a verbal reprimand was in order. But to do nothing? I have no excuse. After a pregnant pause, and with what was probably a ridiculous expression, I mentioned the incident to the guy behind the front desk. He went to check it out, but I left before his investigation concluded.

*******

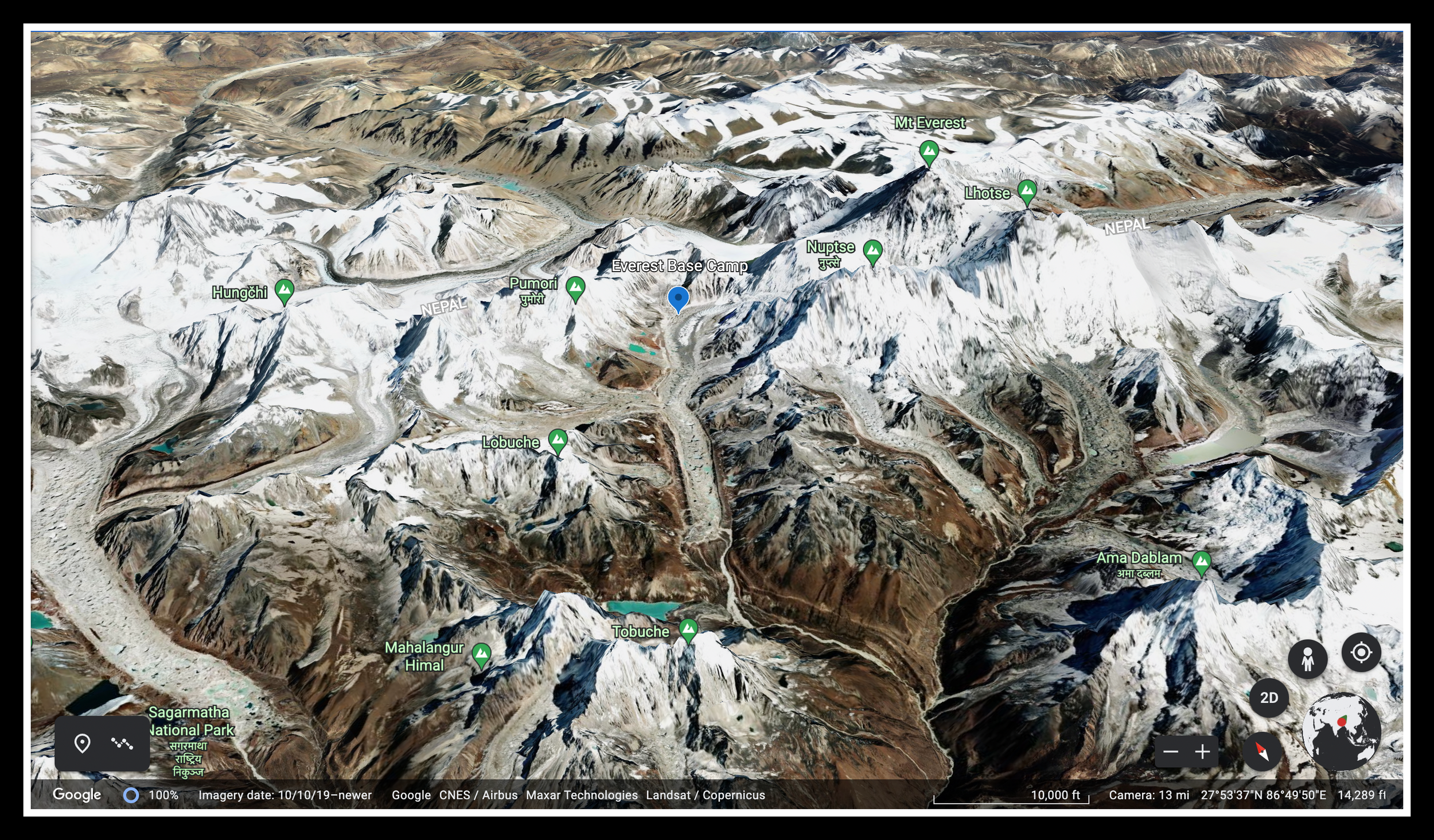

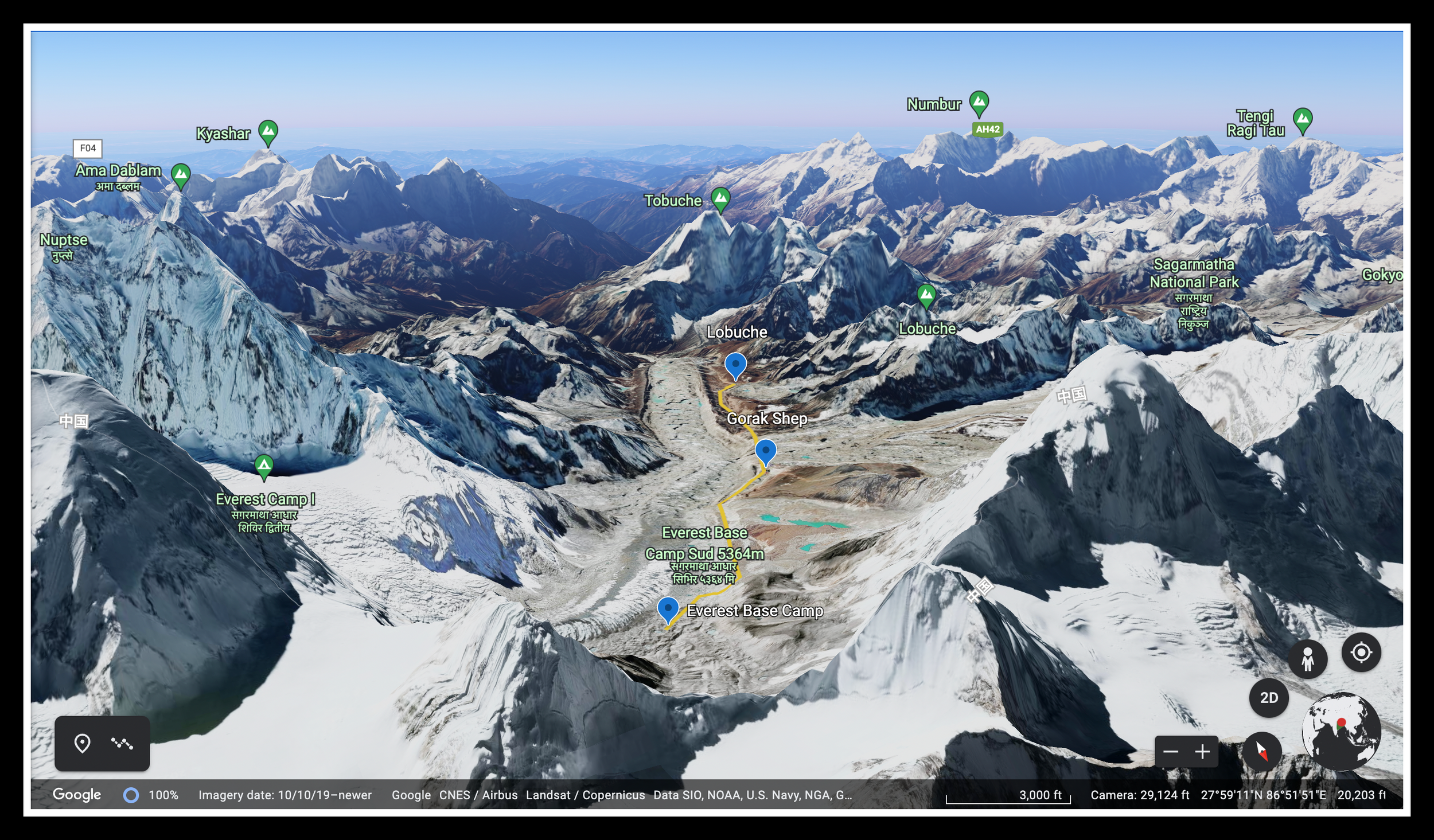

The morning after arriving in Lobuche was a new day and a new me. Resurrection! Still not 100%, but much improved. The trail to Gorak Shep was half a morning’s trek away. I dropped my belongings at a lodge and headed toward Everest Base Camp South (EBC). By then, the revitalization process was complete. Eating breakfast twice and going to bed at 6:30 p.m. had a hand in the revival. The walk to EBC first skirts the glacier, at least until you scamper atop the moraine.

My expectations concerning EBC weren’t grandiose. I'd heard mixed reviews. The Lonely Planet recommended doing Kala Pattar or EBC, warning both might be too much for most. I considered skipping base camp in favor of a longer stay on Kala Pattar and the immediate area. I sensed a tourist trap in EBC, a trip undertaken only to obtain the signature rubber stamp of “been there, done that” feel good emotion about standing at the gateway to the highest mountain on earth. Many people do it for the sake of doing it, but, as I learned over and over, don’t believe everything you read and “many people” are often idiots.

EBC is, in my humble opinion, stupefying and worth every effort, though if you stop at the cairn and prayer flags marking EBC, you could be forgiven for being underwhelmed… maybe. The problem, if there is one, is the comparison with all the staggering scenery experienced on the trek from Lukla. It can be stimulus overload, though I never grew calloused to the panoramas.

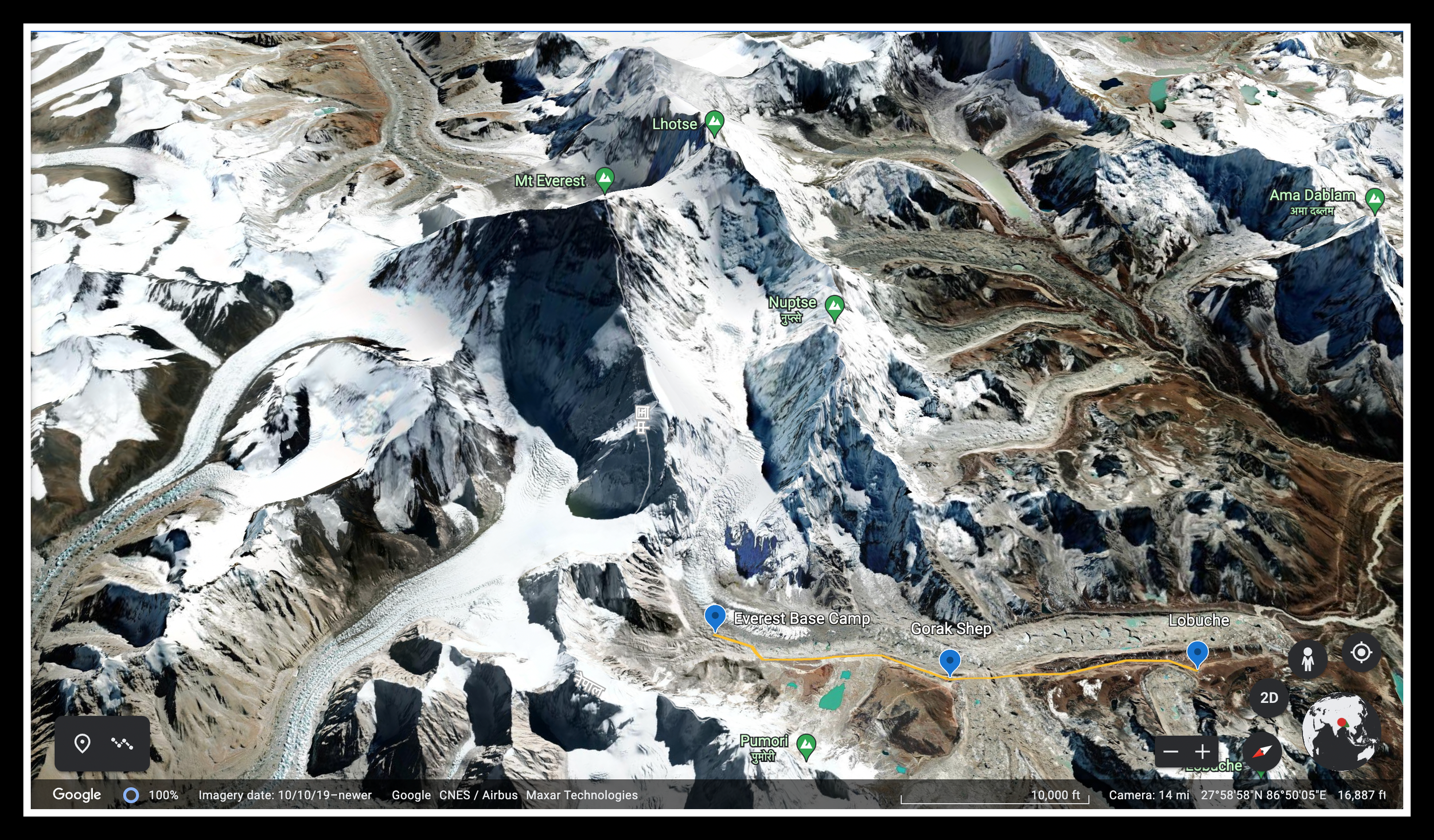

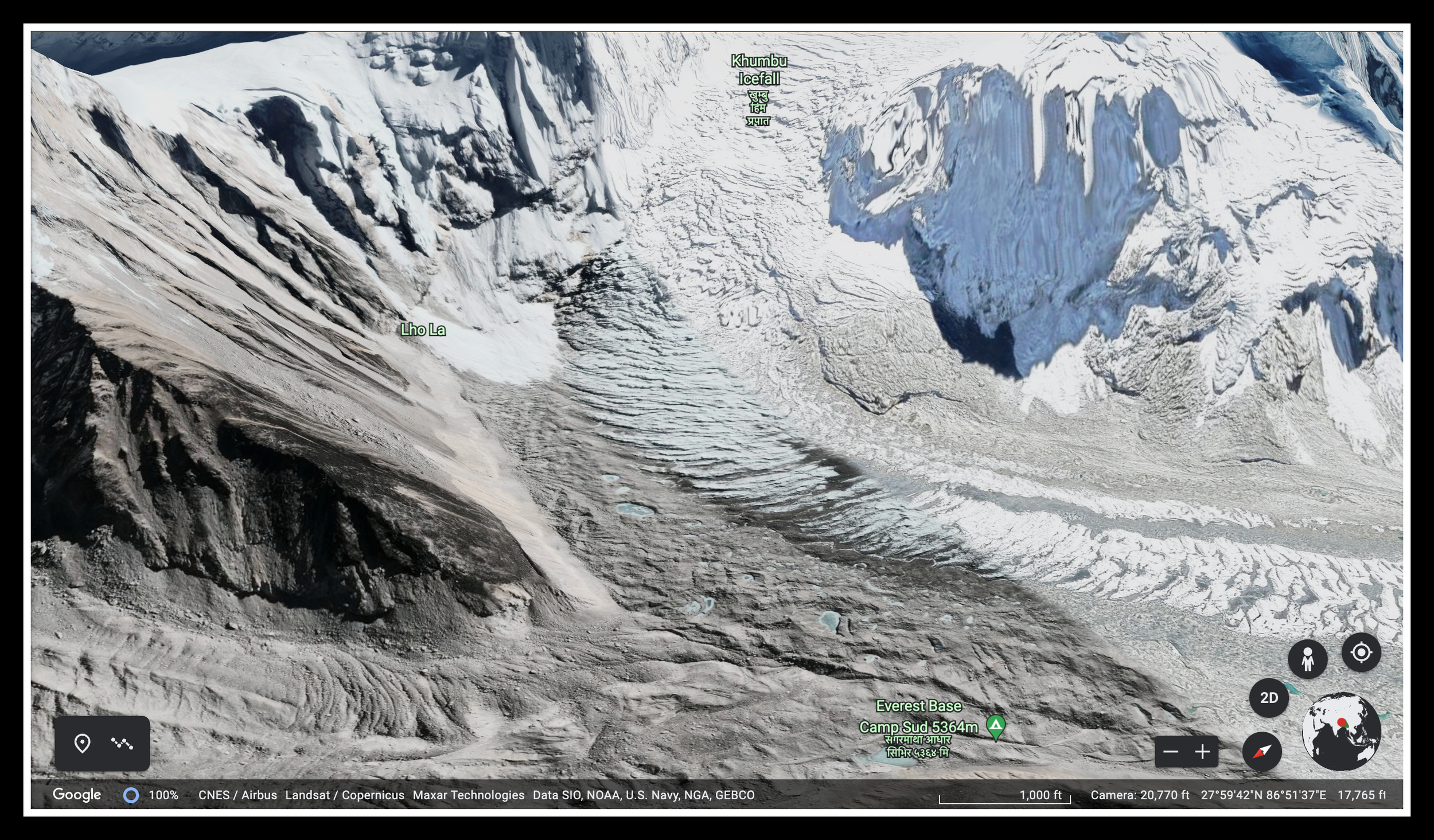

From the initial marker, it’s another 30-40 minutes of hiking along the glacial moraine to the base of the Khumbu Icefall. That initial marker marks the end of EBC, not its beginning. During the climbing season, the entire stretch becomes a makeshift city, packed to the brim with Everest hopefuls. The extra hike makes all the difference. I figured I’d linger at EBC for an hour, but when I reached the bottom of the icefall, I knew the afternoon was booked.

A dead-end valley for the majority, a springboard to Olympus for the brave (or foolhardy) few. The Khumbu Icefall will bend your mind if you stare long enough. The mere thought is remarkable. All that ice shifting like a super slow motion glacial tango—creaking, cracking, and doing all the things respectable glaciers do. The route through the icefall to Camp I is a perilous one, not to be overlooked or underestimated. Hard not to fantasize about the climb while standing so close to the start. For the price of a fully-loaded luxury SUV, it can all be yours.

Although early in the season, one expedition (American) was setting up on the hottest real estate around—right beneath the icefall. A cooking and dining tent with a few shiny yellow North Face tents sat dwarfed by the magnificence. As I approached from the rear, I heard a familiar voice. Suspicions were confirmed when I spotted a unicycle. Unicycle Steve had arrived. (We first crossed paths in Pangboche.) He’d met folks along the way and accompanied them on the trail. The couple he befriended had the good fortune of spending a night at base camp. They were friends with a member of the American expedition team assaulting Everest that year. None of the members were there yet, only the Sherpa contingent making preparations.

I sat. I gaped. I “ooo-ed.” I “ahhh-ed.” I breathed. I soaked up a billion years of tectonic turbulence. Would it have been better without the tent intrusions? I don’t think so. The structures paled in comparison to all that titanic grandeur. The contrast was striking, the insignificance of our existence palpable. During high season, EBC is a veritable three-ring circus of freneticism. I’m sure that’s a sight worth beholding as well, but I was grateful to experience the valley before the masses.

After two hours of staring into the glacial abyss and beyond, I joined Unicycle Steve for the trot back to Gorak Shep. Curiosity slowed our return. We stopped for pictures of random ice formations, to listen to an avalanche or two, and otherwise examine the surreal terrain of the Khumbu Glacier. Much of it resembles a plastic 3-D topographical map, like an oversized model of a larger mountain range.

Steve, an Englishman from Manchester, began unicycling ten years before we met. It was a gift from his wife. The rest, as they say, was history. A fish to water is an apt cliche. He started taking it everywhere. The Khumbu Region was less than ideal, but he managed short bursts of agility in some single track-esque portions of the path, the Kala Pattar trail being of particular note.

He’d once unicycled from Lhasa, Tibet to Kathmandu, Nepal to raise money for a Nepali NGO. He even got his sons in on the act, much to the chagrin of his wife. They’d been at it from the time they were three years old. You know what they say, a family that unicycles together, stays together.

Steve’s bewilderment at the panning of EBC by fellow travelers matched mine. We just couldn’t fathom the criticism given the natural beauty engulfing us, though we did construct a working theory. Many folks underestimate the physical exertion required to tromp through the Himalayas, a mistake not entirely of their own making. Travel agencies, guides, and anyone else associated with the tourist industry in Nepal downplay the hardships to encourage everyone and their mother to visit. So, it’s not surprising people reaching the Khumbu in a state of hypoxic exhaustion dismiss the grandeur with a, “Yes, yes. Very nice. Good. Great. Everest Base Camp? Awesome. Look at that. Wow! Can we go back to my lodge now, so I can pass out and die… pleeease?

As if to underscore the point, we met a Canadian gent going to the icefall. He stopped to have a chat. I thought this a bit queer (as in odd or strange). The time was around 4:00 p.m. The sun, already playing hide-and-seek between clouds, would set around 6:00 p.m. and disappear behind the valley much earlier. He was alone, underdressed, and appeared not to have water. I was trying to read Steve's face for signs of astonishment, but I got nothing. The man's guide told him he was “pretty fast” and could get to EBC in two hours or less. Nuh-uh. Steve calmly explained this was not possible, to which Team Canada responded with, "But you have a unicycle." Um… ‘kay. Steve, still calm, pointed out he was carrying it, as it was too dodgy to play circus. Steve tried, with verbal support from yours truly, to dissuade our new friend from continuing. He highlighted things like the inevitable drop in temperature, the tendency for small rocks to fall from the cliffs later in the day after the sun has had the chance to soften the frozen dirt, the fact that he was solo, the diminishing light, so on and so forth.

Our efforts were in vain. He strode onward. We were dumbfounded. It was like he read a list of everything not to do while in the Himalayas and incorporated it into one hike. We laughed all the way back. That’s not to say we weren’t concerned, but what could we do, wrestle him to the ground, hogtie him to Steve's unicycle, and drag his misguided ass to Gorak Shep? We figured there was a fifty-fifty chance we would be reading about a Canadian gone astray in the next edition of the Lonely Planet. We crossed our fingers.

(I ran into our friend the next day on Kala Pattar. He’d heeded our advice and turned around. He made a point of saying, "I'm not an idiot, ya know?" Never doubted you for an instant.)

Though a magnificent day, one that lives on in my memory, it was not without heartbreak. I lost the ridiculous hat I’d somehow held onto for ten years. I didn’t secure it to my person, so it slipped away. I purchased it in Cusco, Peru. End of an era… sigh.