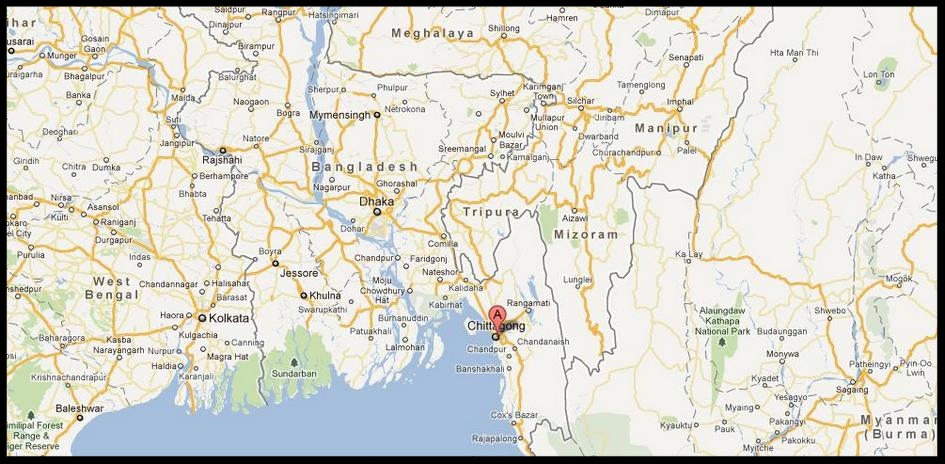

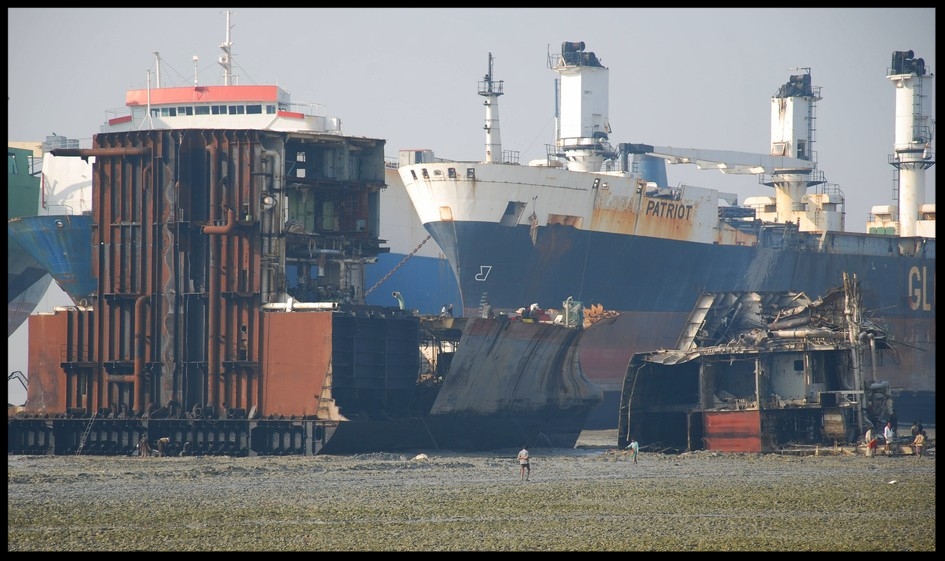

Abandon Ship (Chittagong Ship-Breaking Yards, Bangladesh)

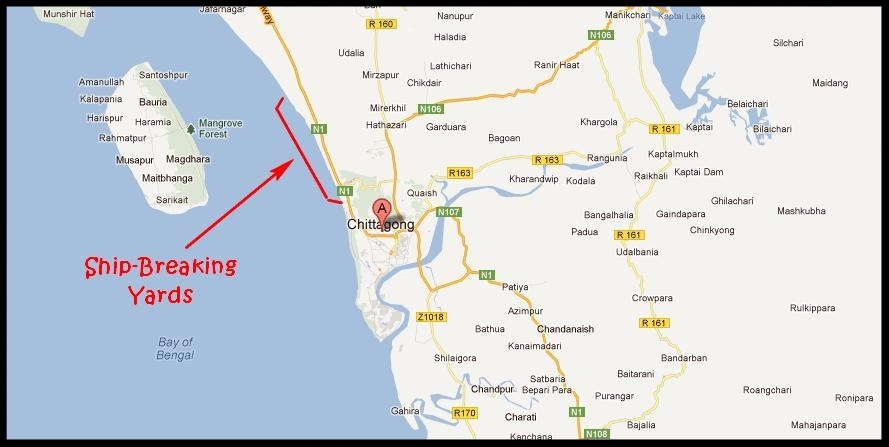

I WAS SKEPTICAL. Rahmat made it sound like getting access to the shipyards north of Chittagong would be easy peasy. Why the skepticism? Well, the ship-breaking yards are controversial. When the cost to refit a vessel exceeds its value, its sentenced to death by disembowelment and disintegration, then sold for scrap. Each ship is a mini environmental disaster waiting to happen, i.e. toxic chemicals and materials galore. The developed world’s insistence on regulations make recycling unprofitable, and that’s before you even get to labor laws.

Bangladesh has neither impediment. This has drawn attention from journalists and ire from environmentalists. Neither are welcome and anyone with a camera is suspect, ergo my skepticism.

Rahmat, an employee at my hotel, was an amiable fellow. Not long into a friendly exchange, he promised an up close and personal look at the shipyards. I didn’t doubt his sincerity, but I wasn’t sure he could deliver. Still, this was more promising than my original plan to head north with a compact camera and a shitload of perseverance. With little to lose, I agreed to meet out front the next morning.

After breakfast, I found Rahmat waiting for me with a CNG taxi (autorickshaw). Again, I was assured access and an opportunity to take unlimited photos.

He wasn’t bullshitting.

A half-hour drive later, we took a left down a dirt road that snaked through a village and eventually ended at some corrugated tin kiosks catering to shipyard workers. He told me to wait in the taxi while he surveyed the situation, recommending I hide my Nikon until we were closer. I did as he suggested and wore my camera under my shirt.

After a few moments, he ushered me forward and together we walked through a porous tin barricade. Nobody stopped us. At any moment I expected someone to intervene and send my ass packing.

But no…

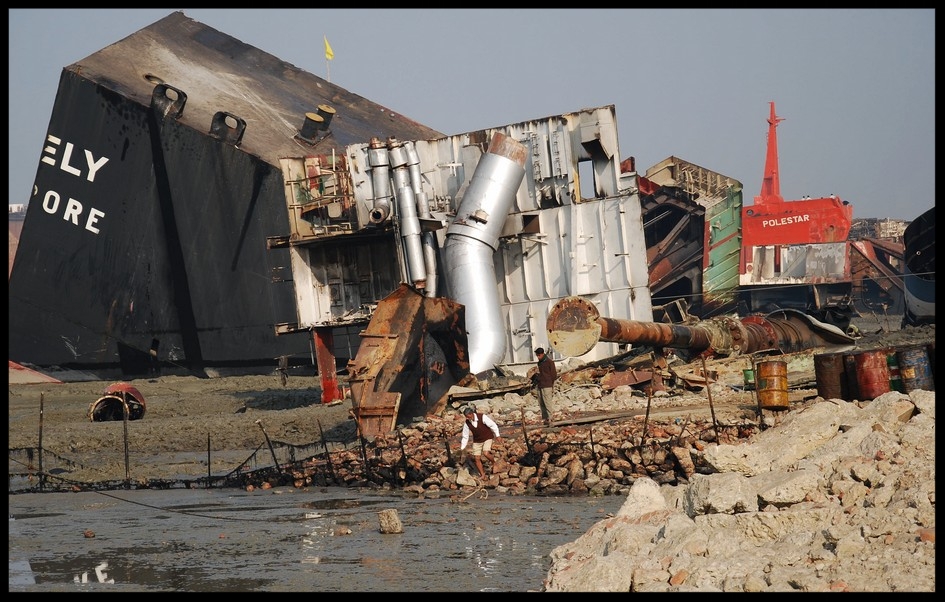

And there I was. As far as I could see were gargantuan vessels in varying stages of deconstruction stranded in the mud. Welcome to Dystopia, Dorothy. We approached a gentleman who appeared to hold a supervisory role. Again, I predicted vigorous protest. Again, I was wrong.

Although uneasy for the first twenty minutes, my concerns were unwarranted. The “friend” he spoke of was his cousin. And the supervisor? His uncle. Rahmat himself was a former employee. Ummm, jackpot. I was given free rein. Not only did I snap a bazillion photos, I also shot video. Everyone was at ease with my presence. Many even requested I photograph them. I assume Rahmat assured them I wasn’t a journalist or activist, but I’m still shocked they were so nonchalant, especially after all my research. They seemed oblivious to the controversy.

So, what did I see? More like what didn't I see.

Supertankers and large ocean-going vessels are driven full speed ahead until beached as close as possible to the high tide line. Once that happens, there’s no going back. All sales are final. This is still a considerable distance from the shore; workers are required to trod through the mud and begin their efforts where the ships come to rest. As they’re torn asunder, many of the pieces, chunks, and fragments are dragged to the coast via metal sheets and ropes. Primary engine? Manpower.

There was a small section of a ship being dismantled in my immediate vicinity. Tools of choice? Sledgehammers and blowtorches. A few workers were so excited they motioned for me to climb aboard and join them. Probably not a smart move, but I couldn’t resist. I climbed an unstable metal ladder and inspected the operation. As I stood imagining what it would be like doing this day in and day out with little or no safety gear, a skittish supervisor (Rahmat’s uncle) thought it a bit much, imploring me to descend. No reason to push my luck, so I complied.

The shipyards have no shortage of danger. It’s everywhere. Rahmat said people died the week before (four if memory serves) and that severe injury and death were common. Labor is cheap, regulations illusory or non-existent. Some “men” working there had conspicuously youthful appearances. Appearances were not deceiving. I discovered a thirteen year old in the mix, and I’m certain a few others were no older than ten or eleven.

I asked Rahmat why he worked there, and why he'd quit. Family strife (his father had been beating him) forced him to run away. This is where he ran. As you might guess, the pay is substantial for the unskilled underprivileged. He earned six thousand taka (eighty-five dollars) per month. Decent pay, but that's roughly three dollars a day to risk life and limb every day. He was fortunate, middle of the wage scale. The children I encountered fared much worse. According to Rahmat, they were lucky to earn fifty dollars per month. I’m sure the salary “skyrockets” if you have a skill (welding, metal working, equipment operator, etc.), but this is not so for most.

Three months was his limit. The danger was too high, so he quit and returned home. It was unclear (language barrier) if he ever told his parents where he'd been. He is hoping to find work in Dubai, but the visa fee is prohibitive (two to three hundred dollars) and his hotel gig wasn’t cutting it. Will Rahmat return to the yards? Tough to say. I certainly hope not.

After taking some shots of the shoreline and vicinity, I wondered if it was possible to go further out. No problem. We doffed our footwear and slithered seaward. Not only was the mud slippery, but we had to be on guard for pieces of protruding metal and other hidden hazards. Prudence dictated I follow close behind Rahmat. In addition to the physical dangers, I can only imagine what noxious chemicals are embedded in the sludge. I hear PCB-laced mud does wonders for skin rejuvenation.

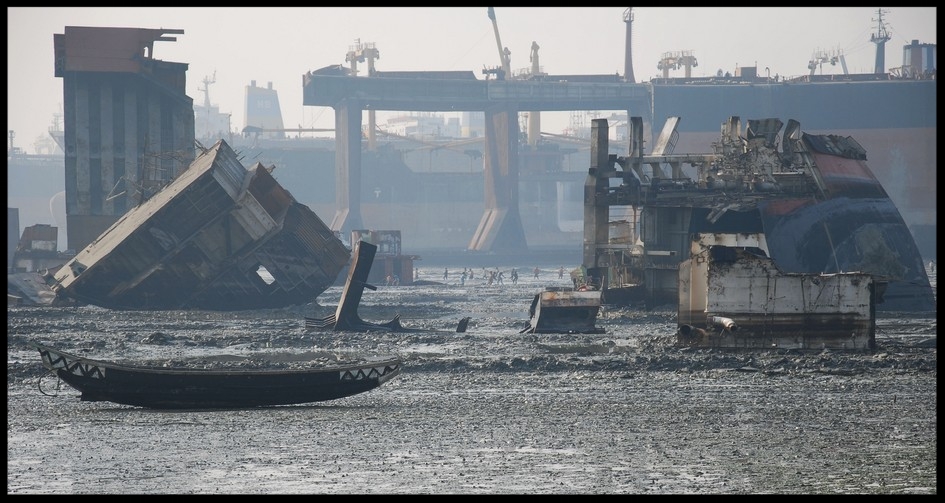

What a spectacle. On one side was a large ship with its skeleton exposed and on the other silent leviathans awaiting execution of their sentence. Partial corpses were strewn about, each disintegrating day by day as pieces were removed and carried away.

In the distance, I saw workers going about their duties, appearing like ants juxtaposed alongside the behemoths of the sea. Hard to believe flesh and blood humans are capable of felling such giants. It seems a proper task for Titans or twenty-third-century robots, not mere mortals.

So, I stood in the mud trying to digest the scene. Any way you slice it, there’s a perpetual human tragedy unfolding. Children without a childhood? Men without a choice? A government without a conscience? No, too shallow. Nothing is ever that simple. Child labor is a terrible reality, but what other options are there? Take away their jobs and where does that leave them? Their families? Is hazardous work better than no work at all? Increase oversight. Increase safety standards. Lower profits. Lower wages. Choices. Terrible, terrible choices. You could blame the government I suppose, but before pulling that trigger you might want to delve into the history of this star-crossed nation. You’ll find suffering and catastrophe on a Grecian scale. There’s a reason Henry Kissinger once referred to Bangladesh as the “basket case of Asia”.

J. D. Salinger once wrote (Franny and Zooey), “And I can't be running back and forth forever between grief and high delight.” Grief and high delight. I spent the morning sprinting between them. The kindness. The warmth. The friendly curiosity. Those smiles. Those goddamn smiles wrapped in irony, pathos, longing, hope, and a dozen other emotions and sentiments that strum the proverbial heartstrings like a gorilla hammering a harpsichord. I was so grateful for the experience, for the hospitality. I was given a rare glimpse into a world few recognize or understand. The reality weighed me down as I said my goodbyes and thanked everyone repeatedly.

Lifeboat orphanage. All those lifeboats. No one to save.

We made a pit stop at one of the many secondhand shops selling anything and everything related to life on the sea. Barometers, clinometers, clocks, sextants, compasses, nautical telescopes, radios, wooden steering wheels, and maps were all on display. A child in the toy store. That was me. Unfortunately, Rahmat had to get back to work, so I had no time to unbury the treasures I knew lay within. I would return the following day with a fellow traveler, Andy, in tow. And Andy came to shop. In light of all his purchases, the owner looked favorably upon me, selling me a brass hand-held telescope for the bargain price of fourteen dollars. Well, it felt like a bargain. It was probably the “you're too ignorant know the difference” price. Heavy, semi-bulky, and scandalously impractical. But it was mine. I was only missing an eye patch, a hook, and peg leg. Next time…Arrrrrrgh!!!